- Home

- Jorge Luis Borges

The Book of Fantasy Page 2

The Book of Fantasy Read online

Page 2

And so it is that Jorge Luis Borges’s own poems and stories, his reflections, his libraries, labyrinths, forking paths, and amphisbaenae, his books of tigers, of rivers, of sand, of mysteries, of changes, have been and will be honored by so many readers for so long: because they are beautiful, because they are nourishing, because they do supremely well what poems and stories do, fulfilling the most ancient, urgent function of words, just as the I Ching and the Dictionary do: to form for us ‘mental representations of things not actually present,’ so that we can form a judgment of what world we live in and where we might be going in it.

URSULA K. LE GUIN, 1987

Sennin*

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1892—1927), Japanese writer. Before taking his own life, he calmly explained the reasons which brought him to this decision and compiled a list of historical suicides, in which he included Christ. His works include Grotesque and Curious Tales, The Three Treasures, Kappa, Rashomon, Japanese Short Stories. He translated the works of Robert Browning into Japanese.

My dear young readers, I am stopping in Osaka now, so I will tell you a story connected with this town.

Once upon a time there came to the town of Osaka a certain man who wanted to be a domestic servant. I do not know his real name, they only remember him by the common servant’s name of Gonsuké, for he was, after all, a servant of all work.

Now this man—we’ll call him Gonsuké, too—entered a ‘WE CAN GET YOU ANY JOB’ office and said to the clerk in charge, who was puffing at his long bamboo pipe:

‘Please, Mr Clerk, I wish to become a sennin. Would you kindly find me a family where I could learn the secret while working as a servant?’

The clerk remained speechless for a while as if astonished at his client’s tall order.

‘Didn’t you hear me, Mr Clerk?’ said Gonsuké, ‘I wish to become a sennin. Will you find me a family where I could learn the secret while working as a servant?’

‘We’re very sorry to disappoint you,’ the clerk drawled, beginning to puff again at his forgotten pipe, ‘but not once in our long business career have we undertaken to find a situation for aspirants to your Senninship! Suppose you go round to another place, then perhaps . . .’

Here Gonsuké edged closer to him on his petulant blue-pantalooned knees, and began to argue in this way:

‘Now, now, mister, that isn’t quite honest, is it? What does your signboard say, anyhow? It says, “WE CAN GET YOU ANY JOB” in so many words. Since you promise us any job, you ought to find us no matter what kind of jobs we may ask for. But now, you may have lied about it all along, intentionally.’

His argument being quite reasonable, the clerk could not very well blame him for his angry outburst.

‘I can assure you, Mr Stranger, there’s no trick there. It’s all straight,’ the clerk pleaded hastily, ‘but if you insist on your strange request I must beg you to come round to us again tomorrow. We’ll make inquiries today at all likely places we can think of.’

The clerk could see no other way out of it than to give him the promise and get him away, for the present anyhow. Needless to say, however, he had not the faintest idea, how could he indeed, of any household where they could teach their servant the secrets of Senninship. So on getting rid of the visitor, the clerk hastened to a physician living near his place.

To him he told the story of his strange client, and then asked in an anxious pleading tone, ‘Now, please, Doctor, what sort of family do you think could train a fellow into a sennin, and that very quickly?’

The question apparently puzzled the doctor. He remained a while in pensive silence, arms folded across his chest, vaguely looking at a big pine-tree in the garden. It was the doctor’s helpmate, a very shrewd woman, better known as Old Vixen, who answered for him, uninivited, on hearing the clerk’s story: ‘Why, nothing can be simpler. Send him on to us. We’ll make him a sennin in a couple of years.’

‘Will you, really, ma’am? That’s great! Really I can’t thank you enough for your kind offer. But frankly, I felt certain from the first that a doctor and a sennin were somehow closely related to each other.’

The clerk, who was blissfully ignorant of her design, bowed his thanks again and again, and left in great glee.

Our doctor followed him out with his eyes, looking as sour as anything, and then, turning round on his wife, brayed peevishly:

‘You silly old woman, do you realize what a foolish thing you’ve gone and said, now? What the dickens would you do if the bumpkin should begin to complain some day that we hadn’t taught him a scrap of your holy trick after so many years?’

But his wife, far from asking his pardon, turned up her nose at him, and quacked, ‘Pugh! You dullard, you’d better mind your own business. A fellow who is as stupidly simple as you could hardly scrape enough in this eat-or-be-eaten world to keep body and soul together.’ This counter-attack succeeded, and she pecked her husband into silence.

The next morning, as had been agreed upon, the clerk brought his boorish client to the doctor’s. Country-bred as he was, Gonsuké came this particular day ceremoniously dressed in haori and hakama, perhaps in honour of this important occasion of his first day. Outwardly, however, he was in no way different from the ordinary peasant. His very commonness must have been a bit of a surprise to the doctor, who had been expecting to see something unusual in a would-be sennin. He eyed him curiously as one might a rare exotic animal such as a musk-deer brought over from far-off India, and then said, ‘I am told that you wish to be a sennin, and I’m very curious to know whatever has put such a notion into your head.’

‘Well, sir, I haven’t much to tell there,’ replied Gonsuké. ‘Indeed it was quite simple. When I first came up to this town and looked at the great big castle, I just thought like this: that even our great ruler Taiko who lives up there must die some day; that you may live in the grandest way imaginable, but still you must come to dust like the rest of us. Well, in short, that all our life is a fleeting dream is just what I felt then.’

‘Then,’ Old Vixen promptly put in her word, ‘you’d do anything if you could only be a sennin?’

‘Yes, madam, if only I could be one.’

‘Very good; then you’ll live here and work for us for twenty years from today, and you shall be the happy possessor of the secrets at the end of your term.’

‘Really, madam? I’m indeed very much obliged to you.’

‘But,’ she added, ‘for twenty years to come you won’t get a penny from us as wages. Is that understood?’

‘Yes, ma’am, thanks, ma’am. I agree to all that.’

In this way started Gonsuké’s twenty-year-service at the doctor’s. He would draw water from the well, chop firewood, prepare every meal, and do all the scrubbing and sweeping for the family. But this was not all, for he would follow the doctor on his rounds, carrying a big medicine-chest on his back. Yet for all this labour Gonsuké never asked for a single penny. Indeed nowhere in Japan could you have found a better servant for less wages.

At last the twenty long years passed, and Gonsuké, again ceremoniously dressed in his family-crested haori as when he first came to them, presented himself before his master and mistress. To them he expressed his cordial thanks for all their kindness to him during the past twenty years. ‘And now, sir,’ he went on, ‘would you kindly teach me today, as you promised twenty years ago today, how to become a sennin and attain eternal youth and immortality?’

‘Here’s a go,’ sighed the doctor to himself at this request. After having worked him twenty long years for nothing, how in the name of humanity could he tell his servant now, that really he knew nothing of the way to Senninship? The doctor wriggled himself out of the dilemma, saying that it was not he but his wife who knew the secrets. ‘So you must ask her to tell you,’ he concluded, and turned woodenly away.

His wife, however, was sweetly unperturbed.

‘Very well, then, I’ll teach you,’ she said, ‘but, mind, you must do what I tell you, however diffic

ult it may seem. Otherwise you could never be a sennin, and besides, you’ll then have to work for us another twenty years without pay, or believe me, God Almighty will strike you dead on the spot.’

‘Very good, madam, I’ll do anything, however difficult it may be,’ replied Gonsuké. He was now hugely delighted, and waited for her to give the word.

‘Well then,’ she said, ‘climb that pine-tree in the garden.’

Utter stranger as she undoubtedly was to Senninship, her intentions may have been simply to impose any impossible task on him, and, in case of his failure, to secure his free services for another twenty years. At her order, however, Gonsuké started climbing the tree without a moment’s hesitation.

‘Go up higher,’ she called after him, ‘no, still higher, right up to the top.’

Standing near the edge of the verandah, she craned her neck to get a better view of her servant on the tree and now saw his haori fluttering high up among the topmost boughs of that very tall pine-tree.

‘Now let go your right hand.’

Gonsuké gripped the bough with his left hand the tighter, and then let go his right in a gingerly sort of way.

‘Next, let go your left hand as well!’

‘Come, come, my good woman,’ said her husband at last, now peering his anxious face upward from behind her. ‘You know, with his left hand off the bough the bumpkin must fall to the ground. And right below there’s the big stone, and he’s a dead man as sure as I’m a doctor.’

‘Right now I want none of your precious advice. Leave everything to me. — Hey, man, off with your left hand, do you hear?’

No sooner had she given the word than Gonsuké pushed away his hesitant left hand. Now with both hands off the bough, how could he stay on the tree? The next moment, as the doctor and his wife caught their breath, Gonsuké, yes, and his haori, too, were seen to come off the bough, and then . . . And then, why, w-w-what’s this?—he stopped, he stopped! in mid-air, instead of dropping like a brick, and stayed on up in the bright noonday sky, posing like a marionette. ‘I thank you both from the very bottom of my heart. You’ve made me a Sennin,’ said Gonsuké from far above.

He was seen to make a very polite bow to them, and then he started climbing higher and higher, softly stepping on the blue sky, until he became a mere dot and disappeared in the fleecy clouds.

What became of the doctor and his wife no one knows. But the big pine-tree in their garden is known to have lived on for a long time, for it is told that a couple of centuries later a Yodoya Tatsugoro who wanted to see the tree clad in snow went to the trouble and expense of having the big tree, which was then more than twenty feet round, transplanted in his own garden.

A Woman Alone with Her Soul

Thomas Bailey Aldrich, North American poet and novelist, was born in New Hampshire in 1835 and died in Boston in 1907. He was the author of Cloth of Gold (1874), Wyndham Tower (1879) and An Old Town by the Sea (1893).

A woman is sitting alone in a house. She knows she is alone in the whole world: every other living thing is dead. The doorbell rings.

Ben-Tobith

Leonid Andreyev, (1871-1919) studied law at the universities of Moscow and St Petersburg but, after depressions which led to several suicide attempts, turned to writing, encouraged by Gorki. His sensational themes, treated in a highly realistic manner, made his reputation; amongst his works are In the Fog (1902) and The Red Laugh (1904), as well as numerous plays.

On that dread day, when a universal wrong was wrought, and Jesus Christ was crucified between two thieves on Golgotha—on that day the teeth of Ben-Tobith, a trader of Jerusalem, had begun to ache unbearably from the earliest hours of the morning.

That toothache had begun even the day before, toward evening: at first his right jaw had begun to pain him slightly, while one tooth (the one just before the wisdom tooth) seemed to have become a little higher and, whenever the tongue touched it, felt a trifle painful. After supper, however, the ache had subsided entirely; Ben-Tobith forgot all about it and felt rather on good terms with the world—he had made a profitable deal that day, exchanging his old ass for a young and strong one, was in a very merry mood, and had not considered the ill-boding symptoms of any importance.

And he had slept very well and most soundly, but just before the dawn something had begun to trouble him, as though someone were rousing him to attend to some very important matter, and when Ben-Tobith angrily awoke, his teeth were aching, aching frankly and malevolently, in all the fullness of a sharp and piercing pain. And by now he could not tell whether it was only the tooth that had bothered him yesterday or whether other teeth had also made common cause with it: all his mouth and his head were filled with a dreadful sensation of pain, as though he were compelled to chew a thousand red-hot, sharp nails.

He took a mouthful of water from a clay jug: for a few moments the raging pain vanished; the teeth throbbed and undulated, and this sensation was actually pleasant in comparison with what he had felt before. Ben-Tobith lay down anew, bethought him of his newly acquired young ass, reflected how happy he would be if it were not for those teeth of his, and tried his best to fall asleep. But the water had been warm, and five minutes later the pain returned, raging worse than before, and Ben-Tobith sat up on his pallet and swayed to and fro like a pendulum. His whole face puckered up and was drawn toward his prominent nose, while on the nose itself, now all white from his torments, hung a bead of cold sweat.

And thus, swaying and groaning from his pain, did he greet the first rays of that sun which was fated to behold Golgotha with its three crosses and then grow dim from horror and grief.

Ben-Tobith was a good man and a kindly, with little liking for wronging anybody, yet when his wife awoke he told her many unpleasant things, even though he was barely able to open his mouth, and complained that he had been left alone like a jackal, to howl and writhe in his pain. His wife accepted the unmerited reproaches with patience, since she realized that they were not uttered from an evil heart, and brought him many excellent remedies, such as purified rat droppings, to be applied to the cheek, a pungent infusion of scorpions, and a true shard of the tablets of the law, splintered off at the time Moses had shattered them.

The rat droppings eased the pain a little, but not for long; it was the same way with the infusion and the shard, for each time, after a short-lived relief, the pain returned with new vigor. And during the brief moments of respite Ben-Tobith consoled himself by thinking of the young ass and making plans concerning it, while at such times as his teeth worsened he moaned, became wroth with his wife, and threatened to dash his brains out against a stone if the pain would not abate. And all the while he kept pacing up and down the flat roof of his house, but avoided coming too near the edge thereof for very shame, since his whole head was swathed, like a woman’s, in a shawl.

The children came running to him several times and, speaking very fast, told him something or other about Jesus of Nazareth. Ben-Tobith would stop his pacing and listen to them for a few moments with his face puckering but then stamp his foot in anger and drive them from him; he was a kindhearted man and loved children, but now he was wroth because they annoyed him with all sorts of trifles.

Nor was that the only unpleasant thing: the street, as well as all the roofs near by, were crowded with people who did not have a single thing to do, apparently, but stare at Ben-Tobith with his head swathed, like a woman’s, in a shawl. And he was just about to come down from the roof when his wife told him:

‘Look there—they’re leading the robbers. Maybe that will make thee forget thy pain.’

‘Leave me in peace, woman. Canst thou not see how I suffer?’ Ben-Tobith answered her surlily.

But the words of his wife held out a vague hope that his toothache might let up, and he grudgingly approached the parapet of his roof. Putting his head to one side, shutting one eye and propping up his sore cheek with his hand, he made a wry, weepy face, and looked down.

An enormous mob, raising great dust an

d an incessant din, was going helter-skelter through the narrow street that ran uphill. In the midst of this mob walked the malefactors, bending under the weight of their crosses, while the lashes of the Roman legionaries writhed over their heads like black serpents. One of the condemned—that fellow with the long, light hair, his seamless chiton all torn and stained with blood—stumbled against a rock that had been thrown under his feet and fell. The shouts grew louder, and the motley crowd, like an iridescent sea, closed over the fallen man.

Ben-Tobith shuddered from pain—it was just as though someone had plunged a red-hot needle into his tooth and then given that needle a twist for good measure. He let out a long-drawn moan: ‘Oo-oo-oo!’ and left the parapet, wryly apathetic and in a vile temper.

‘Hearken to them screaming!’ he enviously mumbled, picturing to himself the widely open mouths, with strong teeth that did not ache, and imagined what a shout he himself would set up if only he were well.

And because of that mental picture his pain became ferocious, while his head bobbed fast, and he began to low like a calf: ‘Moo-oo-oo!’

‘They say He restored sight to the blind,’ said Ben-Tobith’s wife, who was glued to the parapet, and she skimmed a pebble toward the spot where Jesus, who had risen to his feet under the lashes, was now moving slowly.

‘Yea, verily! If he would but rid me of my toothache it would suffice,’ Ben-Tobith retorted sarcasticially, and added with a bitterness begotten of irritation: ‘Look at the dust they are raising! For all the world like a drove of cattle. Somebody ought to take a stick to them and disperse them! Take me downstairs, Sarah.’

The good wife turned out to be right: the spectacle had diverted Ben-Tobith somewhat, although it may have been the rat droppings that had helped at last, and he succeeded in falling asleep. And when he awoke, the pain had practically vanished, and there was only a gumboil swelling on his right jaw, so small a gumboil that one could hardly notice it. His wife said that it was altogether unnoticeable, but Ben-Tobith smiled slyly at that: he knew what a kindhearted wife he had, and how she liked to say things that would please the hearer. Samuel the tanner, a neighbor, dropped in, and Ben-Tobith took him to see his young ass and listened with pride to the tanner’s warm praises of the animal and its master.

Labyrinths

Labyrinths Collected Fictions

Collected Fictions The Garden of Forking Paths

The Garden of Forking Paths The Widow Ching-Pirate

The Widow Ching-Pirate Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others)

Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others) Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

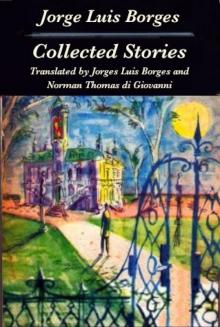

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Collected Stories

Collected Stories Ficciones

Ficciones Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 The Widow Ching—Pirate

The Widow Ching—Pirate Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Borges at Eighty: Conversations

Borges at Eighty: Conversations The Book of Fantasy

The Book of Fantasy