- Home

- Jorge Luis Borges

The Book of Fantasy

The Book of Fantasy Read online

VIKING

http://www.penguin.com/publishers/vikingbooks/

Published by the Penguin Group

Viking Penguin Inn, 40 West 23rd Street, New York, New York 10010, U.S.A.

Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 2801 John Street, Markham, Ontario, Canada L3R 1B4

Penguin Books (N.Z.) Ltd, 182—190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

First published in 1988 by Viking Penguin Inc.

Published simultaneously in Great Britain by Xanadu Publications Limited

Copyright © The Estate of Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, The Estate of

Silvina Ocampo, and Xanadu Publications Limited, 1988

Foreword copyright © Ursula K. Le Guin, 1988

All rights reserved

Antología de la Literatura Fantástica first published in Argentina 1940

Revised 1965, 1976

Copyright © 1940, 1965, 1976 Editorial Sudamericana

Sources and Acknowledgments constitute an extension of this copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Antología de la literatura fantástica. English.

The book of fantasy.

Translation of: Antología de la literatura fantástica.

Includes bio-bibliographies.

1. Fantastic literature. I. Borges, Jorge Luis,

1899—1986. II. Ocampo, Silvina. III. Bioy Casares,

Adolfo. IV. Title.

PN6071.F25A5513 1988 808.83‘876 88-40100

Designed by Richard Glyn Jones

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may

be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form

or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without

the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Introduction by Ursula K. Le Guin

Sennin Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

A Woman Alone with Her Soul Thomas Bailey Aldrich

Ben-Tobith Leonid Andreyev

The Phantom Basket John Aubrey

The Drowned Giant J. G. Ballard

Enoch Soames Max Beerbohm

The Tail of the Sphinx Ambrose Bierce

The Squid in Its Own Ink Adolfo Bioy Casares

Guilty Eyes Ah’med Ech Chiruani

Anything You Want!… Léon Bloy

Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius Jorge Luis Borges

Odin Jorge Luis Borges and Delia Ingenieros

The Golden Kite, The Silver Wind Ray Bradbury

The Man Who Collected the First of September, 1973 Tor Åge Bringsværd

The Careless Rabbi Martin Buber

The Tale and the Poet Sir Richard Burton

Fate is a Fool Arturo Cancela and Pilar de Lusarreta

An Actual Authentic Ghost Thomas Carlyle

The Red King’s Dream Lewis Carroll

The Tree of Pride G. K. Chesterton

The Tower of Babel G. K. Chesterton

The Dream of the Butterfly Chuang Tzu

The Look of Death Jean Cocteau

House Taken Over Julio Cortazar

Being Dust Santiago Dabove

A Parable of Gluttony Alexandra David-Neel

The Persecution of the Master Alexandra David-Neel

The Idle City Lord Dunsany

Tantalia Macedonio Fernández

Eternal Life James George Frazer

A Secure Home Elena Garro

The Man Who Did Not Believe in Miracles Herbert A. Giles

Earth’s Holocaust Nathaniel Hawthorne

Ending for a Ghost Story I.A. Ireland

The Monkey’s Paw W. W. Jacobs

What is a Ghost? James Joyce

May Goulding James Joyce

The Wizard Passed Over Infante Don Juan Manuel

Josephine the Singeror the Mouse Folk Franz Kafka

Before the Law Franz Kafka

The Return of Imray Rudyard Kipling

The Horses of Abdera Leopoldo Lugones

The Ceremony Arthur Machen

The Riddle Walter de la Mare

Who Knows? Guy de Maupassant

The Shadow of the Players Edwin Morgan

The Cat H. A. Murena

The Story of the Foxes Niu Chiao

The Atonement Silvina Ocampo

The Man Who Belonged to Me Giovanni Papini

RANI Carlos Peralta

The Blind Spot Barry Perowne

The Wolf Caius Petronius Arbitrus

The Bust Manuel Peyrou

The Cask of Amontillado Edgar Allan Poe

The Tiger of Chao-ch‘êng P’U Sung Ling

How We Arrived at the Island of Tools François Rabelais

The Music On The Hill Saki (H. H. Munro)

Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched May Sinclair

The Cloth which Weaves Itself W. W. Skeat

Universal History William Olaf Stapledon

A Theologian In Death Emmanuel Swedenborg

The Encounter From the T’ang Dynasty

The Three Hermits Count Leo Tolstoy

Macario B. Traven

The Infinite Dream of Pao-Yu Ts’ao Chan (Hsueh Ch’in)

The Mirror of Wind-to-Moon Ts’ao Chan (Hsueh Ch’in)

The Desire to be a Man Villiers de L’isle Adam

Memnon,or Human Wisdom Voltaire

The Man Who Liked Dickens Evelyn Waugh

Pomegranate Seed Edith Wharton

Lukundoo Edward Lucas White

The Donguys Juan Rodolfo Wilcock

Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime Oscar Wilde

The Sorcerer of the White Lotus Lodge Richard Wilhelm

The Celestial Stag G. Willoughby-Meade

Saved by the Book G. Willoughby-Meade

The Reanimated Englishman Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley

The Sentence Wu Ch’eng En

The Sorcerers William Butler Yeats

Fragment José Zorrilla

SOURCES AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Introduction

by Ursula K. Le Guin

There are two books which I look upon as esteemed and cherished great-aunts or grandmothers, wise and mild though sometimes rather dark of counsel, to be turned to when the judgment hesitates for want of material to form itself upon. One of these books provides facts, of a peculiar sort. The other does not. The I Ching or Book of Changes is the visionary elder who has outlived fact, the Ancestor so old she speaks a different tongue. Her counsel is sometimes appallingly clear, sometimes very obscure indeed. ‘The little fox crossing the river wets its tail,’ she says, smiling faintly, or, ‘A dragon appears in the field,’ or, ‘Biting upon dried gristly meat . . .’ One retires to ponder long upon such advice. The other Auntie is younger, and speaks English—indeed, she speaks more English than anybody else. She offers fewer dragons and much more dried gristly meat. And yet the Oxford English Dictionary, or A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, is also a Book of Changes. Most wonderful in its transmutations, it is not a Book of Sand, yet is inexhaustible; not an Aleph, yet all we can ever say is there, if we can but find it.

‘Auntie!’ I say (magnifying glass in hand, because my edition, the Compact Auntie, is compressed into two volumes of terrifyingly small print)—‘Auntie! please tell me about fantasy, because I want to talk about The Book of Fantasy, but I am not sur

e what I am talking about.’

‘Fantasy, or Phantasy,’ replies Auntie, clearing her throat, ‘is from the Greek ϕαντασία, lit. “a making visible.” ’ She explains that ϕαντασία, is related to ϕαντάζειν, ‘to make visible,’ or in Late Greek, ‘to imagine, have visions,’ and to ϕαίνειν, ‘to show.’ And she summarizes the older uses of the word in English: an appearance, a phantom, the mental process of sensuous perception, the faculty of imagination, a false notion, caprice, or whim. Then, though she eschews the casting of yarrow stalks or coins polished with sweet oil, being after all an Englishwoman, she begins to tell the Changes: the mutations of a word moving through the minds of people moving through the centuries. She shows how a word that to the Schoolmen of the late Middle Ages meant ‘the mental apprehension of an object of perception,’ that is, the mind’s very act of linking itself to the phenomenal world, came in time to signify just the reverse—an hallucination, or a phantasm, or the habit of deluding oneself. After which, doubling back on its tracks like a hare, the word fantasy was used to mean the imagination, ‘the process, the faculty, or the result of forming mental representations of things not actually present.’ This definition seems very close to the Scholastic sense of fantasy, but leads, of course, in quite the opposite direction—going so far in that direction, these days, as often to imply that the representation is extravagant, or visionary, or merely fanciful. (Fancy is fantasy’s own daughter, via elision of the penult; while fantastic is a sister-word with a family of her own.)

So fantasy remains ambiguous; it stands between the false, the foolish, the delusory, the shallows of the mind, and the mind’s deep connection with the real. On this threshold sometimes it faces one way, masked and beribboned, frivolous, an escapist; then it turns, and we glimpse as it turns the face of an anel, bright truthful messenger, arisen Urizen.

Since the Oxford English Dictionary was compiled, the tracks of the word fantasy have been complicated still further by the comings and goings of psychologists. The technical uses in psychology of fantasy and phantasy have deeply influenced our sense and use of the word; and they have also given us the handy verb to fantasize. But Auntie does not acknowledge the existence of that word. Into the Supplement, through the back door, she admits only fantasist; and she defines the newcomer, politely but with, I think, a faint curl of the lip, as ‘one who “weaves” fantasies.’ One might think that a fantasist was one who fantasizes, but it is not so. Currently, one who fantasizes is understood either to be daydreaming, or to be using the imagination therapeutically as a means of discovering reasons Reason does not know, discovering oneself to oneself. A fantasist is one who writes a fantasy for others. But the element of discovery is there, too.

Auntie’s use of ‘weave’ may be taken as either patronizing or quaint, for writers don’t often say nowadays that they ‘weave’ their works, but bluntly that they write them. Fantasists earlier in the century, in the days of victorious Realism, were often apologetic about what they did, offering it as something less than ‘real’ fiction—mere fancywork, bobble-fringing to literature. More fantasists are rightly less modest now that what they do is generally recognized as literature, or at least as a genre of literature, or at least as a genre of subliterature, or at least as a commercial product. For fantasies are rife and many-colored on the bookstalls. The head of the fabled Unicorn is laid upon the lap of Mammon, and the offering is acceptable to Mammon. Fantasy, in fact, has become quite a business.

But when one night in Buenos Aires in 1937 three friends sat talking together about fantastic literature, it was not yet a business. Nor was it even known as fantastic literature, when one night in a villa in Geneva in 1818 three friends sat talking together, telling one another ghost stories. They were Mary Shelley, her husband Percy, and Lord Byron—and Claire Clairmont was probably with them, and the strange young Dr Polidori—and they told awful tales, and Mary Shelley was frightened. ‘We will each,’ cried Byron, ‘write a ghost story!’ So Mary went away and thought about it, fruitlessly, until a few nights later she dreamed a nightmare in which a ‘pale student’ used strange arts and machineries to arouse from unlife the ‘hideous phantasm of a man.’ And so, alone of the friends, she wrote her ghost story, Frankenstein: or, A Modern Prometheus, which I think is the first great modern fantasy. There are no ghosts in it; but fantasy, as the Dictionary showed us, is often seen as ghoulie-mongering. Because ghosts inhabit, or haunt, one part of the vast domain of fantastic literature, both oral and written, people familiar with that corner of it call the whole thing Ghost Stories, or Horror Tales; just as others call it Fairyland after the part of it they know or love best, and others call it Science Fiction, and others call it Stuff and Nonsense. But the nameless being given life by Dr Frankenstein’s, or Mary Shelley’s, arts and machineries is neither ghost nor fairy, and science-fictional only in intent; stuff and nonsense he is not. He is a creature of fantasy, archetypal, deathless. Once raised he will not sleep again, for his pain will not let him sleep, the unanswered moral questions that woke with him will not let him rest in peace. When there began to be money in the fantasy business, plenty of money was made out of him in Hollywood, but even that did not kill him. If his story were not too long for this anthology, it might well be here; very likely it was mentioned on that night in 1937 in Buenos Aires, when Jorge Luis Borges, Adolfo Bioy Casares, and Silvina Ocampo fell to talking—so Casares tells us—‘about fantastic literature . . . discussing the stories which seemed best to us. One of us suggested that if we put together the fragments of the same type we had listed in our notebooks, we would have a good book. As a result we drew up this book . . . simply a compilation of stories from fantastic literature which seemed to us to be the best.’

So that, charmingly, is how The Book of Fantasy came to be, fifty years ago. Three friends talking. No plans, no definitions, no business, except the intention of ‘having a good book.’ Of course, in the making of such a book by such makers, certain definitions were implied by inclusion, and by exclusion other definitions were ignored; so one will find, perhaps for the first time, horror and ghosts and fairy and science-fiction stories all together within the covers of The Book of Fantasy; while any bigot wishing to certify himself as such by dismissing it as all stuff and nonsense is tacitly permitted to do so. The four lines in the book by Chuang Tzu should suffice to make him think twice, permanently.

It is an idiosyncratic selection, and completely eclectic. Some of the stories will be familiar to anyone who reads, others are exotic discoveries. A very well-known piece such as ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ seems less predictable, set among works and fragments from the Orient and South America and distant centuries, by Kafka, Swedenborg, Cortázar, Agutagawa, Niu Chiao; its own essential strangeness is restored to it. There is some weighting towards writers, especially English writers, of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which reflects, I imagine, the taste of the anthologizers and perhaps particularly that of Borges, who was himself a member and direct inheritor of the international tradition of fantasy which included Kipling and Chesterton.

Perhaps I should not say ‘tradition,’ since it has no name as such and little recognition in critical circles, and is distinguished in college English departments mainly by being ignored; but I believe that there is a company of fantasists that Borges belonged to even as he transcended it, and which he honored even as he transformed it. As he included these older writers in The Book of Fantasy, it may be read truly as his ‘notebook’ of sources and affiliations and elective affinities. Some chosen, such as Bloy or Andreyev, may seem rather heavyhanded now, but others are treasurable. The Dunsany story, for instance, is not only very beautiful, as the early poetry of Yeats is beautiful, but is also, fascinatingly, a kind of miniature or concave-mirror of the anthology itself. The book is full of such reflections and interconnections. Beerbohm’s familiar tale of ‘Enoch Soames,’ read here, seems to involve and concern other writings and writers in the book; so that

I now believe that when people gather in the Reading Room of the British Library on June 3rd, 1997, to wait for poor Enoch’s phantom and watch him discover his Fungoids, still ignored by critics and professors and the heartless public, still buried ignominious in the Catalogue,—I believe that among those watching there will be other phantoms; and among those, perhaps, Borges. For he will see then, not as through a glass, darkly.

If in the 1890s fantasy appeared to be a kind of literary fungus-growth, if in the 1920s it was still perceived as secondary, if in the 1980s it has been degraded by commercial exploitation, it may well seem quite safe and proper to the critics to ignore it. And yet I think that our narrative fiction has been going slowly and vaguely and massively, not in the wash and slap of fad and fashion but as a deep current, for years, in one direction, and that that direction is the way of fantasy. An American fiction writer now may yearn toward the pure veracity of Sarah Orne Jewett or Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, as an English writer, such as Margaret Drabble, may look back with longing to the fine solidities of Bennett; but the limited and rationally perceived societies in which those books were written, and their shared language, are lost. Our society—global, multilingual, enormously irrational—can perhaps describe itself only in the global, intuitional language of fantasy.

So it may be that the central ethical dilemma of our age, the use or non-use of annihilating power, was posed most cogently in fictional terms by the purest of fantasists. Tolkien began The Lord of the Rings in 1937 and finished it about ten years later. During those years, Frodo withheld his hand from the Ring of Power, but the nations did not.

So it is that Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities serves many of us as a better guidebook to our world than any Michelin or Fodor’s.

So it is that the most revealing and accurate descriptions of our daily life in contemporary fiction may be shot through with strangeness, or displaced in time, or set upon imaginary planets, or dissolved into the phantasmagoria of drugs or of psychosis, or may rise from the mundane suddenly into the visionary and as simply descend from it again.

So it is that the ‘magical realists’ of South America are read for their entire truthfulness to the way things are, and have lent their name as perhaps the most fitting to the kind of fiction most characteristic of our times.

Labyrinths

Labyrinths Collected Fictions

Collected Fictions The Garden of Forking Paths

The Garden of Forking Paths The Widow Ching-Pirate

The Widow Ching-Pirate Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others)

Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others) Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

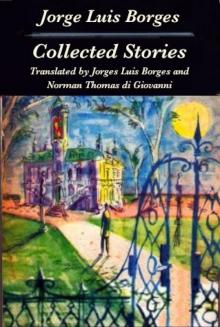

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Collected Stories

Collected Stories Ficciones

Ficciones Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 The Widow Ching—Pirate

The Widow Ching—Pirate Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Borges at Eighty: Conversations

Borges at Eighty: Conversations The Book of Fantasy

The Book of Fantasy