- Home

- Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Page 2

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Read online

Page 2

BURGIN: Do you remember much from your childhood?

BORGES: You see, I was always very shortsighted, so when I think of my childhood, I think of books and the illustrations in books. I suppose I can remember every illustration in Huckleberry Finn and Life on the Mississippi and Roughing It and so on. And the illustrations in the Arabian Nights. And Dickens—Cruikshank and Fisk illustrations. Of course, well, I also have memories of being in the country, of riding horseback in the estancia on the Uruguay River in the Argentine pampas. I remember my parents and the house with the large patio and so on. But what I chiefly seem to remember are small and minute things. Because those were the ones that I could really see. The illustrations in the encyclopedia and the dictionary, I remember them quite well. Chambers Encyclopaedia or the American edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica with the engravings of animals and pyramids.

BURGIN: So you remember the books of your childhood better than the people.

BORGES: Yes, because I could see them.

BURGIN: You’re not in touch with any people that you knew from your childhood now? Have you had any lifelong friends?

BORGES: Well, some school companions from Buenos Aires and then, of course, my mother, she’s ninety-one; my sister who’s three years, three or four years, younger than I am, she’s a painter. And then, most of my relatives—most of them have died.

BURGIN: Had you read much before you started to write or did your writing and reading develop together?

BORGES: I’ve always been a greater reader than a writer. But, of course, I began to lose my eyesight definitely in 1954, and since then I’ve done my reading by proxy, no? Well, of course, when one cannot read, then one’s mind works in a different way. In fact, it might be said that there is a certain benefit in being unable to read, because you think that time flows in a different way. When I had my eyesight, then if I had to spend say a half an hour without doing anything, I would go mad. Because I had to be reading. But now, I can be alone for quite a long time, I don’t mind long railroad journeys, I don’t mind being alone in a hotel or walking down the street, because, well, I won’t say that I am thinking all the time because that would be bragging.

I think I am able to live with a lack of occupation. I don’t have to be talking to people or doing things. If somebody had gone out, and I had come here and found the house empty, then I would have been quite content to sit down and let two or three hours pass and go out for a short walk, but I wouldn’t feel especially unhappy or lonely. That happens to all people who go blind.

BURGIN: What are you thinking about during that time—a specific problem or …

BORGES: I could or I might not be thinking about anything, I’d just be living on, no? Letting time flow or perhaps looking back on memories or walking across a bridge and trying to remember favourite passages, but maybe I wouldn’t be doing anything, I’d just be living. I never understand why people say they’re bored because they have nothing to do. Because sometimes I have nothing whatever to do, and I don’t feel bored. Because I’m not doing things all the time, I’m content.

BURGIN: You’ve never felt bored in your life?

BORGES: I don’t think so. Of course, when I had to be ten days lying on my back after an operation I felt anguish, but not boredom.

BURGIN: You’re a metaphysical writer and yet so many writers like, for example, Jane Austen or Fitzgerald or Sinclair Lewis, seem to have no real metaphysical feeling at all.

BORGES: When you speak of Fitzgerald, you’re thinking of Edward Fitzgerald, no? Or Scott Fitzgerald?

BURGIN: Yes, the latter.

BORGES: Ah, yes.

BURGIN: I was just naming a writer who came to mind as having essentially no metaphysical feeling.

BORGES: He was always on the surface of things, no? After all, why shouldn’t you, no?

BURGIN: Of course, most people live and die without ever, it seems, really thinking about the problems of time or space or infinity.

BORGES: Well, because they take the universe for granted. They take things for granted. They take themselves for granted. That’s true. They never wonder at anything, no? They don’t think it’s strange that they should be living. I remember the first time I felt that was when my father said to me, “What a queer thing,” he said, “that I should be living, as they say, behind my eyes, inside my head, I wonder if that makes sense?” And then, it was the first time I felt that, and then instantly I pounced upon that because I knew what he was saying. But many people can hardly understand that. And they say, “Well, but where else could you live?”

BURGIN: Do you think there’s something in people’s minds that blocks out the sense of the miraculous, something maybe inherent in most human beings that doesn’t allow them to think about these things? Because, after all, if they spent their time thinking about the miracle of the universe, they wouldn’t do the work civilization depends on and nothing, perhaps, would get done.

BORGES: But I think that today too many things get done.

BURGIN: Yes, of course.

BORGES: Sarmiento wrote that he once met a gaucho and the gaucho said to him, “The countryside is so lovely that I don’t want to think about its cause.” That’s very strange, no? It’s a kind of non sequitur, no? Because he should have begun to think about the cause of that beauty. But I suppose he meant that he drank all those things in, and he felt quite happy about them, and he had no use for thinking. But generally speaking, I think men are more prone to metaphysical wondering than women. I think that women take the world for granted. Things for granted. And themselves, no? And circumstances for granted. I think circumstances especially.

BURGIN: They confront each moment as a separate entity without thinking about all the circumstances that lead up to it.

BORGES: No, because they think of …

BURGIN: They take things one at a time.

BORGES: Yes, they take them one at a time, and then they’re afraid of cutting a poor figure, or they think of themselves as being actresses, no? The whole world looking at them and, of course, admiring them.

BURGIN: They do seem to be more self-conscious than men on the whole.

BORGES: I have known very intelligent women who are quite incapable of philosophy. One of the most intelligent women I know, she’s one of my pupils; she studies Old English with me, well, she was wild over so many books and poets, then I told her to read Berkeley’s dialogues, three dialogues, and she could make nothing of them. And then I gave her a book of William James, some problems of philosophy, and she’s a very intelligent woman, but she couldn’t get inside the books.

BURGIN: They bored her?

BORGES: No, she didn’t see why people should be poring over things that seemed very simple to her. So I said, “Yes, but are you sure that time is simple, are you sure that space is simple, are you sure that consciousness is simple?” “Yes,” she said. “Well, but could you define them?” She said, “No, I don’t think I could, but I don’t feel puzzled by them.” That, I suppose, is generally what a woman would say, no? And she was a very intelligent woman.

BURGIN: But, of course, there seems to be something in your mind that hasn’t blocked out this basic sense of wonder.

BORGES: No.

BURGIN: In fact, it’s at the centre of your work, this astonishment at the universe itself.

BORGES: That’s why I cannot understand such writers as Scott Fitzgerald or Sinclair Lewis. But Sinclair Lewis has more humanity, no? I think besides that he sympathizes with his victims. When you read Babbitt, well, perhaps I think in the end, he became one with Babbitt. For as a writer has to write a novel, a very long novel with a single character, the only way to keep the novel and hero alive is to identify with him. Because if you write a long novel with a hero you dislike or a character that you know very little about, then the book falls to pieces. So, I suppose, that’s what happened to Cervantes in a way. When he began Don Quixote he knew very little about him and then, as he went on, he had to identify himsel

f with Don Quixote, he must have felt that, I mean, that if he got a long distance from his hero and he was always poking fun at him and seeing him as a figure of fun, then the book would fall to pieces. So that, in the end, he became Don Quixote. He sympathized with him against the other creatures, well, against the Innkeeper and the Duke, and the Barber, and the Parson, and so on.

BURGIN: So you think that remark of your father’s heralded the beginning of your own metaphysics?

BORGES: Yes, it did.

BURGIN: How old were you then?

BORGES: I don’t know. I must have been a very young child. Because I remember he said to me, “Now look here; this is something that may amuse you,” and then, he was very fond of chess, he was a good chess player, and then he took me to the chessboard, and he explained to me the paradoxes of Zeno, Achilles and the Tortoise, you remember, the arrows, the fact that movement was impossible because there was always a point in between, and so on. And I remember him speaking of these things to me and I was very puzzled by them. And he explained them with the help of a chessboard.

BURGIN: And your father had aspired to be a writer, you said.

BORGES: Yes, he was a professor of psychology and a lawyer.

BURGIN: And a lawyer also.

BORGES: Well, no, he was a lawyer, but he was also a professor of psychology.

BURGIN: Two separate disciplines.

BORGES: Well, but he was interested in psychology and he had no use for the law. He told me once that he was quite a good lawyer but that he thought the whole thing was a bag of tricks and that to have studied the Civil Code he may as well have tried to learn the laws of whist or poker, no? I mean they were conventions and he knew how to use them, but he didn’t believe in them. I remember my father said to me something about memory, a very saddening thing. He said, “I thought I could recall my childhood when we first came to Buenos Aires, but now I know that I can’t.” I said, “Why?” He said, “Because I think that memory”—I don’t know if this was his own theory, I was so impressed by it that I didn’t ask him whether he found it or whether he evolved it—but he said, “I think that if I recall something, for example, if today I look back on this morning, then I get an image of what I saw this morning. But if tonight, I’m thinking back on this morning, then what I’m really recalling is not the first image, but the first image in memory. So that every time I recall something, I’m not recalling it really, I’m recalling the last time I recalled it, I’m recalling my last memory of it. So that really,” he said, “I have no memories whatever, I have no images whatever, about my childhood, about my youth. And then he illustrated that, with a pile of coins. He piled one coin on top of the other and said, “Well, now this first coin, the bottom coin, this would be the first image, for example, of the house of my childhood. Now this second would be a memory I had of that house when I went to Buenos Aires. Then the third one another memory and so on. And as in every memory there’s a slight distortion, I don’t suppose that my memory of today ties in with the first images I had,” so that, he said, “I try not to think of things in the past because if I do I’ll be thinking back on those memories and not on the actual images themselves.” And then that saddened me. To think maybe we have no true memories of youth.

BURGIN: That the past was invented, fictitious.

BORGES: That it can be distorted by successive repetition. Because if in every repetition you get a slight distortion, then in the end you will be a long way off from the issue. It’s a saddening thought. I wonder if it’s true, I wonder what other psychologists would have to say about that.

BURGIN: I’m curious about some of your early books that haven’t been translated into English, such as Historia de la eternidad (History of Eternity). Are you still fond of those books?

BORGES: No, I think, as I said in the foreword, that I would have written that book in a very different way. Because I think I was very unfair to Plato. Because I thought of the archetypes as being, well, museum pieces, no? But really, they should be thought of as living, as living, of course, in an everlasting life of their own, in a timeless life. I don’t know why, but when I first read The Republic, when I first read about the types, I felt a kind of fear. When I read, for example, about the Platonic Triangle, that triangle was to me a triangle by itself, no? I mean it didn’t have three equal sides, two equal sides, or three unequal sides. It was a kind of magic triangle made of all those things, and yet not committed to any one of them, no? I felt that the whole world of Plato, the world of eternal beings, was somehow uncanny and frightening. And then what I wrote about the kennings, that was all wrong, because afterwards when I went into Old English, and I made some headway in Old Norse, I saw that my whole theory of them was wrong. And then, in this last book, Nueva antología personal (A Second Personal Anthology), I have added a new article saying that the idea of kennings had come from the literary possibilities discovered in compound words. So that virtually there are very few metaphors, but people remember the metaphors because they’re striking. They forget that when writers, at least in England, began to use kennings, they thought of them chiefly as rather pompous compound words. And then they found the metaphorical possibilities of those compound words.

BURGIN: What about A Universal History of Infamy?

BORGES: Well, that was a kind of—I was head editor of a very popular magazine.

BURGIN: Sur?

BORGES: Yes. Coeditor. And then I wrote a story, I changed it greatly, about a man who liberated slaves and then sold them in the South. I got that out of Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi, and then I invented circumstances and I made a kind of story of it. But all the stories in that book were kind of jokes or fakes. But now I don’t think very much of that book; it amused me when I wrote it, but I can hardly recall who the characters were.

BURGIN: Would you like Historia de la eternidad to be translated, do you think?

BORGES: With due apologies to the reader, yes, explaining that when I wrote that I was a young man and that I made many mistakes.

BURGIN: How old were you when you wrote that?

BORGES: I think I must have been about twenty-nine or thirty, but I matured, if I ever did mature, very, very slowly. But I think I had the luck to begin with the worst mistakes, literary mistakes, a man can make. I began by writing utter rubbish. And then when I found it out I left that kind of rubbish behind. The same thing happened to my friend, Bioy Casares.1 He’s a very intelligent man, but at first every book he published bewildered his friends, because the books were quite pointless, and very involved at the same time. And he said that he had done his best to be straightforward but that every time a book came out it was a thorn in the flesh, because we didn’t know what to say to him about it. And then suddenly he began writing very fine stories. But his first books are so bad that when people come to his house (he’s a rich man) and conversation is flagging, then he goes to his room and he comes back with one of his old books. Of course, he, well, he hides what the book is, no? And then he says, “Look here, I got this book from an unknown writer two or three days ago; let’s see what we can make of it?” And then he reads it, and then people begin to chuckle and they laugh and sometimes he gives the joke away and sometimes he doesn’t, but I know that he’s reading his own old stuff and that he thinks of it as a joke. He even encourages people to laugh at it, and when somebody suspects, they will remember, for example, the name of a character and so on, they’ll say, “Well, look here, you wrote that,” then he says, “Well, really I did, but after all, it’s rubbish; you shouldn’t think that I wrote it, you should enjoy it for the fun of it.”

You see what a nice character he is, no? Because I don’t think many people would do that kind of thing. I would feel very bashful. I would have to be apologizing all the time, but he enjoys the joke, a joke against himself. But that kind of thing is very rare in Buenos Aires. In Colombia it might be done, but not in Buenos Aires, or in Mexico, eh? Because in Mexico they take themselves in deadly earnest, and in

Buenos Aires also. To suggest, for example, that perhaps—you know that we have a national hero called José de San Martín, you may have heard of him, no? The Argentine Academy of History decided that no ill could be spoken of him. I mean he was entitled to a reverence denied to the Buddha or to Dante or to Shakespeare or to Plato or to Spinoza, and that was done quite seriously by grown-up men, not by children. And then I remember a Venezuelan writer wrote that San Martín “Tenía un aire avieso.” Now avieso means “sly,” but rather the bad side, no? And then Capdevila, a good Argentine writer, refuted him in two or three pages, saying that those two words, avieso—sly, cunning, no?—and San Martín, were impossible, because you may as well speak of a square triangle. And then he very gently explained to the other that that kind of thing was impossible. Because to an Argentine mind—he said nothing whatever about a universal mind—the two words were nonsensical. And now, isn’t that very strange; he seems to be a lunatic behaving that way.

BURGIN: What about your book Evaristo Carriego?

BORGES: Well, therein a tale hangs. Evaristo Carriego, as you may have read, was a neighbor of ours, and I felt that there was something in the neighbourhood of Palermo—a kind of slum then, I was a boy, I lived in it—I felt that somehow, something might be made out of it. It even had a kind of wistfulness, because there were childhood memories and so on. And then Carriego was the first poet who ever sang the Buenos Aires slums, and he lived on our side of the woods in Palermo. And I remembered him because he used to come to dinner with us every Sunday. I said, “I’ll write a book about him.” And then my mother very wisely said to me, “After all,” she said, “the only reason you have for writing about Carriego is that he was a friend of your father’s, and a neighbor and that he died of lung disease in 1921. But why don’t you, since you have a year”—because I had won some literary prize or other—“why not write about a really interesting Argentine poet, for example, Lugones.”

Labyrinths

Labyrinths Collected Fictions

Collected Fictions The Garden of Forking Paths

The Garden of Forking Paths The Widow Ching-Pirate

The Widow Ching-Pirate Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others)

Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others) Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

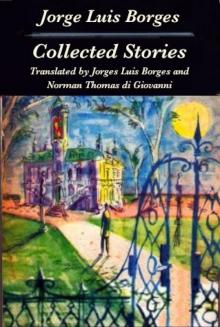

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Collected Stories

Collected Stories Ficciones

Ficciones Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 The Widow Ching—Pirate

The Widow Ching—Pirate Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Borges at Eighty: Conversations

Borges at Eighty: Conversations The Book of Fantasy

The Book of Fantasy