- Home

- Jorge Luis Borges

The Widow Ching—Pirate Page 5

The Widow Ching—Pirate Read online

Page 5

c) a monograph on ‘certain connections or affinities’ between the philosophies of Descartes, Leibniz, and John Wilkins (Nîmes, 1903);

d) a monograph on Leibniz’ Characteristica universalis (Nîmes, 1904);

e) a technical article on the possibility of enriching the game of chess by eliminating one of the rook’s pawns (Menard proposes, recommends, debates, and finally rejects this innovation);

f) a monograph on Ramon Lull’s Ars magna generalis (Nîmes, 1906);

g) a translation, with introduction and notes, of Ruy López de Segura’s Libro de la invención liberal y arte del juego del axedrez (Paris, 1907);

h) drafts of a monograph on George Boole’s symbolic logic;

i) a study of the essential metrical rules of French prose, illustrated with examples taken from Saint-Simon (Revue des langues romanes, Montpellier, October 1909);

j) a reply to Luc Durtain (who had countered that no such rules existed), illustrated with examples taken from Luc Durtain (Revue des langues romanes, Montpellier, December 1909);

k) a manuscript translation of Quevedo’s Aguja de navegar cultos, titled La boussole des précieux;

l) a foreword to the catalog of an exhibit of lithographs by Carolus Hourcade (Nîmes, 1914);

m) a work entitled Les problèmes d’un problème (Paris, 1917), which discusses in chronological order the solutions to the famous problem of Achilles and the tortoise (two editions of this work have so far appeared; the second bears an epigraph consisting of Leibniz’ advice ‘Ne craignez point, monsieur, la tortue,’ and brings up to date the chapters devoted to Russell and Descartes);

n) a dogged analysis of the ‘syntactical habits’ of Toulet (NRF, March 1921) (Menard, I recall, affirmed that censure and praise were sentimental operations that bore not the slightest resemblance to criticism);

o) a transposition into alexandrines of Paul Valéry’s Cimetière marin (NRF, January 1928);

p) a diatribe against Paul Valéry, in Jacques Reboul’s Feuilles pour la suppression de la realité (which diatribe, I might add parenthetically, states the exact reverse of Menard’s true opinion of Valéry; Valéry understood this, and the two men’s friendship was never imperiled);

q) a ‘definition’ of the countess de Bagnoregio, in the ‘triumphant volume’ (the phrase is that of another contributor, Gabriele d’Annunzio) published each year by that lady to rectify the inevitable biases of the popular press and to present ‘to the world and all of Italy’ a true picture of her person, which was so exposed (by reason of her beauty and her bearing) to erroneous and/or hasty interpretations;

r) a cycle of admirable sonnets dedicated to the baroness de Bacourt (1934);

s) a handwritten list of lines of poetry that owe their excellence to punctuation.1

This is the full extent (save for a few vague sonnets of occasion destined for Mme Henri Bachelier’s hospitable, or greedy, album des souvenirs) of the visible lifework of Pierre Menard, in proper chronological order. I shall turn now to the other, the subterranean, the interminably heroic production – the œuvre nonpareil, the œuvre that must remain – for such are our human limitations! – unfinished. This work, perhaps the most significant writing of our time, consists of the ninth and thirty-eighth chapters of Part I of Don Quixote and a fragment of Chapter XXII. I know that such a claim is on the face of it absurd; justifying that ‘absurdity’ shall be the primary object of this note.2

Two texts, of distinctly unequal value, inspired the undertaking. One was that philological fragment by Novalis – number 2005 in the Dresden edition, to be precise – which outlines the notion of total identification with a given author. The other was one of those parasitic books that set Christ on a boulevard, Hamlet on La Cannabière, or don Quixote on Wall Street. Like every man of taste, Menard abominated those pointless travesties, which, Menard would say, were good for nothing but occasioning a plebeian delight in anachronism or (worse yet) captivating us with the elementary notion that all times and places are the same, or are different. It might be more interesting, he thought, though of contradictory and superficial execution, to attempt what Daudet had so famously suggested: conjoin in a single figure (Tartarin, say) both the Ingenious Gentleman don Quixote and his squire …

Those who have insinuated that Menard devoted his life to writing a contemporary Quixote besmirch his illustrious memory. Pierre Menard did not want to compose another Quixote, which surely is easy enough – he wanted to compose the Quixote. Nor, surely, need one be obliged to note that his goal was never a mechanical transcription of the original; he had no intention of copying it. His admirable ambition was to produce a number of pages which coincided – word for word and line for line – with those of Miguel de Cervantes.

‘My purpose is merely astonishing,’ he wrote me on September 30, 1934, from Bayonne. ‘The final term of a theological or metaphysical proof – the world around us, or God, or chance, or universal Forms – is no more final, no more uncommon, than my revealed novel. The sole difference is that philosophers publish pleasant volumes containing the intermediate stages of their work, while I am resolved to suppress those stages of my own.’ And indeed there is not a single draft to bear witness to that years-long labor.

Initially, Menard’s method was to be relatively simple: Learn Spanish, return to Catholicism, fight against the Moor or Turk, forget the history of Europe from 1602 to 1918 – be Miguel de Cervantes. Pierre Menard weighed that course (I know he pretty thoroughly mastered seventeenth-century Castilian) but he discarded it as too easy. Too impossible, rather!, the reader will say. Quite so, but the undertaking was impossible from the outset, and of all the impossible ways of bringing it about, this was the least interesting. To be a popular novelist of the seventeenth century in the twentieth seemed to Menard to be a diminution. Being, somehow, Cervantes, and arriving thereby at the Quixote – that looked to Menard less challenging (and therefore less interesting) than continuing to be Pierre Menard and coming to the Quixote through the experiences of Pierre Menard. (It was that conviction, by the way, that obliged him to leave out the autobiographical foreword to Part II of the novel. Including the prologue would have meant creating another character – ‘Cervantes’ – and also presenting Quixote through that character’s eyes, not Pierre Menard’s. Menard, of course, spurned that easy solution.) ‘The task I have undertaken is not in essence difficult,’ I read at another place in that letter. ‘If I could just be immortal, I could do it.’ Shall I confess that I often imagine that he did complete it, and that I read the Quixote – the entire Quixote – as if Menard had conceived it? A few nights ago, as I was leafing through Chapter XXVI (never attempted by Menard), I recognized our friend’s style, could almost hear his voice in this marvelous phrase: ‘the nymphs of the rivers, the moist and grieving Echo.’ That wonderfully effective linking of one adjective of emotion with another of physical description brought to my mind a line from Shakespeare, which I recall we discussed one afternoon:

Where a malignant and a turban’d Turk …

Why the Quixote? my reader may ask. That choice, made by a Spaniard, would not have been incomprehensible, but it no doubt is so when made by a Symboliste from Nîmes, a devotee essentially of Poe – who begat Baudelaire, who begat Mallarmé, who begat Valéry, who begat M Edmond Teste. The letter mentioned above throws some light on this point. ‘The Quixote,’ explains Menard,

deeply interests me, but does not seem to me – comment dirai-je? – inevitable. I cannot imagine the universe without Poe’s ejaculation ‘Ah, bear in mind this garden was enchanted!’ or the Bateau ivre or the Ancient Mariner, but I know myself able to imagine it without the Quixote. (I am speaking, of course, of my personal ability, not of the historical resonance of those works.) The Quixote is a contingent work; the Quixote is not necessary. I can premeditate committing it to writing, as it were – I can write it – without falling into a tautology. At the age of twelve or thirteen I read it – perhaps read it cover to cover, I cannot recall. S

ince then, I have carefully reread certain chapters, those which, at least for the moment, I shall not attempt. I have also glanced at the interludes, the comedies, the Galatea, the Exemplary Novels, the undoubtedly laborious Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda, and the poetic Voyage to Parnassus … My general recollection of the Quixote, simplified by forgetfulness and indifference, might well be the equivalent of the vague foreshadowing of a yet unwritten book. Given that image (which no one can in good conscience deny me), my problem is, without the shadow of a doubt, much more difficult than Cervantes’. My obliging predecessor did not spurn the collaboration of chance; his method of composition for the immortal book was a bit à la diable, and he was often swept along by the inertiæ of the language and the imagination. I have assumed the mysterious obligation to reconstruct, word for word, the novel that for him was spontaneous. This game of solitaire I play is governed by two polar rules: the first allows me to try out formal or psychological variants; the second forces me to sacrifice them to the ‘original’ text and to come, by irrefutable arguments, to those eradications … In addition to these first two artificial constraints there is another, inherent to the project. Composing the Quixote in the early seventeenth century was a reasonable, necessary, perhaps even inevitable undertaking; in the early twentieth, it is virtually impossible. Not for nothing have three hundred years elapsed, freighted with the most complex events. Among those events, to mention but one, is the Quixote itself.

In spite of those three obstacles, Menard’s fragmentary Quixote is more subtle than Cervantes’. Cervantes crudely juxtaposes the humble provincial reality of his country against the fantasies of the romance, while Menard chooses as his ‘reality’ the land of Carmen during the century that saw the Battle of Lepanto and the plays of Lope de Vega. What burlesque brushstrokes of local color that choice would have inspired in a Maurice Barrès or a Rodríguez Larreta! Yet Menard, with perfect naturalness, avoids them. In his work, there are no gypsy goings-on or conquistadors or mystics or Philip IIs or autos da fé. He ignores, overlooks – or banishes – local color. That disdain posits a new meaning for the ‘historical novel.’ That disdain condemns Salammbô, with no possibility of appeal.

No less amazement visits one when the chapters are considered in isolation. As an example, let us look at Part I, Chapter XXXVIII, ‘which treats of the curious discourse that Don Quixote made on the subject of arms and letters.’ It is a matter of common knowledge that in that chapter, don Quixote (like Quevedo in the analogous, and later, passage in La hora de todos) comes down against letters and in favor of arms. Cervantes was an old soldier; from him, the verdict is understandable. But that Pierre Menard’s don Quixote – a contemporary of La trahison des clercs and Bertrand Russell – should repeat those cloudy sophistries! Mme Bachelier sees in them an admirable (typical) subordination of the author to the psychology of the hero; others (lacking all perspicacity) see them as a transcription of the Quixote; the baroness de Bacourt, as influenced by Nietzsche. To that third interpretation (which I consider irrefutable), I am not certain I dare to add a fourth, though it agrees very well with the almost divine modesty of Pierre Menard: his resigned or ironic habit of putting forth ideas that were the exact opposite of those he actually held. (We should recall that diatribe against Paul Valéry in the ephemeral Surrealist journal edited by Jacques Reboul.) The Cervantes text and the Menard text are verbally identical, but the second is almost infinitely richer. (More ambiguous, his detractors will say – but ambiguity is richness.)

It is a revelation to compare the Don Quixote of Pierre Menard with that of Miguel de Cervantes. Cervantes, for example, wrote the following (Part I, Chapter IX):

… truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor.

This catalog of attributes, written in the seventeenth century, and written by the ‘ingenious layman’ Miguel de Cervantes, is mere rhetorical praise of history. Menard, on the other hand, writes:

… truth, whose mother is history, rival of time, depository of deeds, witness of the past, exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor.

History, the mother of truth! – the idea is staggering. Menard, a contemporary of William James, defines history not as a delving into reality but as the very fount of reality. Historical truth, for Menard, is not ‘what happened’; it is what we believe happened. The final phrases – exemplar and adviser to the present, and the future’s counselor – are brazenly pragmatic.

The contrast in styles is equally striking. The archaic style of Menard – who is, in addition, not a native speaker of the language in which he writes – is somewhat affected. Not so the style of his precursor, who employs the Spanish of his time with complete naturalness.

There is no intellectual exercise that is not ultimately pointless. A philosophical doctrine is, at first, a plausible description of the universe; the years go by, and it is a mere chapter – if not a paragraph or proper noun – in the history of philosophy. In literature, that ‘falling by the wayside,’ that loss of ‘relevance,’ is even better known. The Quixote, Menard remarked, was first and foremost a pleasant book; it is now an occasion for patriotic toasts, grammatical arrogance, obscene de luxe editions. Fame is a form – perhaps the worst form – of incomprehension.

Those nihilistic observations were not new; what was remarkable was the decision that Pierre Menard derived from them. He resolved to anticipate the vanity that awaits all the labors of mankind; he undertook a task of infinite complexity, a task futile from the outset. He dedicated his scruples and his nights ‘lit by midnight oil’ to repeating in a foreign tongue a book that already existed. His drafts were endless; he stubbornly corrected, and he ripped up thousands of handwritten pages. He would allow no one to see them, and took care that they not survive him.3 In vain have I attempted to reconstruct them.

I have reflected that it is legitimate to see the ‘final’ Quixote as a kind of palimpsest, in which the traces – faint but not undecipherable – of our friend’s ‘previous’ text must shine through. Unfortunately, only a second Pierre Menard, reversing the labors of the first, would be able to exhume and revive those Troys …

‘Thinking, meditating, imagining,’ he also wrote me, ‘are not anomalous acts – they are the normal respiration of the intelligence. To glorify the occasional exercise of that function, to treasure beyond price ancient and foreign thoughts, to recall with incredulous awe what some doctor universalis thought, is to confess our own languor; or our own barbarie. Every man should be capable of all ideas, and I believe that in the future he shall be.’

Menard has (perhaps unwittingly) enriched the slow and rudimentary art of reading by means of a new technique – the technique of deliberate anachronism and fallacious attribution. That technique, requiring infinite patience and concentration, encourages us to read the Odyssey as though it came after the Æneid, to read Mme Henri Bachelier’s Le jardin du Centaure as though it were written by Mme Henri Bachelier. This technique fills the calmest books with adventure. Attributing the Imitatio Christi to Louis Ferdinand Céline or James Joyce – is that not sufficient renovation of those faint spiritual admonitions?

Mini Modern Classics

RYŪNOSUKE AKUTAGAWA Hell Screen

KINGSLEY AMIS Dear Illusion

DONALD BARTHELME Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby

SAMUEL BECKETT The Expelled

SAUL BELLOW Him With His Foot in His Mouth

JORGE LUIS BORGES The Widow Ching – Pirate

PAUL BOWLES The Delicate Prey

ITALO CALVINO The Queen’s Necklace

ALBERT CAMUS The Adulterous Woman

TRUMAN CAPOTE Children on Their Birthdays

ANGELA CARTER Bluebeard

RAYMOND CHANDLER Killer in the Rain

EILEEN CHANG Red Rose, White Rose

G. K. CHESTERTON The Strange Crime of John Boulnois

JOS

EPH CONRAD Youth

ROBERT COOVER Romance of the Thin Man and the Fat Lady

ISAK DINESEN [KAREN BLIXEN] Babette’s Feast

MARGARET DRABBLE The Gifts of War

HANS FALLADA Short Treatise on the Joys of Morphinism

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD Babylon Revisited

IAN FLEMING The Living Daylights

E. M. FORSTER The Machine Stops

SHIRLEY JACKSON The Tooth

HENRY JAMES The Beast in the Jungle

M. R. JAMES Canon Alberic’s Scrap-Book

JAMES JOYCE Two Gallants

FRANZ KAFKA In the Penal Colony

RUDYARD KIPLING ‘They’

D. H. LAWRENCE Odour of Chrysanthemums

PRIMO LEVI The Magic Paint

H. P. LOVECRAFT The Colour Out of Space

MALCOLM LOWRY Lunar Caustic

KATHERINE MANSFIELD Bliss

CARSON MCCULLERS Wunderkind

ROBERT MUSIL Flypaper

VLADIMIR NABOKOV Terra Incognita

R. K. NARAYAN A Breath of Lucifer

FRANK O’CONNOR The Cornet-Player Who Betrayed Ireland

DOROTHY PARKER The Sexes

LUDMILLA PETRUSHEVSKAYA Through the Wall

JEAN RHYS La Grosse Fifi

SAKI Filboid Studge, the Story of a Mouse That Helped

ISAAC BASHEVIS SINGER The Last Demon

WILLIAM TREVOR The Mark-2 Wife

JOHN UPDIKE Rich in Russia

H. G. WELLS The Door in the Wall

EUDORA WELTY Moon Lake

P. G. WODEHOUSE The Crime Wave at Blandings

VIRGINIA WOOLF The Lady in the Looking-Glass

STEFAN ZWEIG Chess

a little history

Penguin Modern Classics were launched in 1961, and have been shaping the reading habits of generations ever since.

Labyrinths

Labyrinths Collected Fictions

Collected Fictions The Garden of Forking Paths

The Garden of Forking Paths The Widow Ching-Pirate

The Widow Ching-Pirate Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others)

Short Stories of Jorge Luis Borges - the Giovanni Translations (And Others) Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations

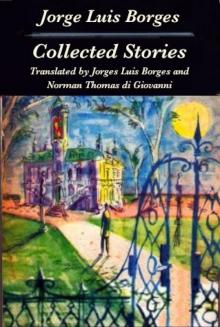

Jorge Luis Borges: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations Collected Stories

Collected Stories Ficciones

Ficciones Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952

Other Inquisitions, 1937-1952 The Widow Ching—Pirate

The Widow Ching—Pirate Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Luis Borges Borges at Eighty: Conversations

Borges at Eighty: Conversations The Book of Fantasy

The Book of Fantasy